I’ve been teaching the Introduction to Geographic Information Systems (GIS) class in the Earth, Environmental, and Sustainability Sciences (EESS) Department for about 11 years. Suresh Muthukrishnan (department chair) also teaches the course. I’ve learned a ton from him. Here are some things I really enjoy about teaching the course:

- Interdisciplinary Nature – Students from across campus take the course. Of course, there are lots of EESS majors. However, even those projects run the gamut. Projects like geologic mapping, landslide risk, sustainable farming, and even mapping data from GPS collars on mountain lions. But students of history, economics, sociology, computer science, business, and music also come up with some great projects.

- The Opportunity to Learn – Every semester, students will come up with novel questions and methods. I think my typical response is, “I haven’t done that before, but I know it’s possible. Let’s figure it out together.” So I learn something new about GIS, as well as all the topics above, each time I teach.

- Community Connections – Many of the projects involve community partners–folks like the Greer Police Department, Upstate Warrior Solution (which serves veterans), Greenlink (our public transportation department), local land conservation non-profits, the forestry department, and community associations. Our first deep partnership involved mapping streetlights, which I’ll talk about in another post.

- Working with Our Post-Baccalaureate Fellows (postbacs) – I’m grateful to get to work with two recent Furman graduates who are on our team. Catherine Lippert (Sustainability Science) and Sam Hayes (History and Politics and International Affairs) are an integral part of teaching the course. They have serious GIS chops and roll up their sleeves to help the students with projects, every step of the way.

- Project-Based Learning – The course involves a semester-long project. It’s a real challenge to teach GIS principles, create meaningful labs, AND support students as they use these concepts and tools to apply what they’ve learned to address a real-world problem. Every semester I think, “We took on too much. This isn’t going to happen.” But it always comes together. Here’s the syllabus for the class.

Here are some examples from a recent class. I don’t want to make it seem like I’m taking credit for these. The students did the work. Catherine, Sam, and I were teammates. However, the examples are illustrative of the range of projects that are possible. The projects are easier to share, now that we have switched the delivery format from poster presentations to StoryMaps.

Charlotte Moore: Transit-Motivated Gentrification: An analysis of gentrification in Over-the-Rhine, especially as a result of the Cincinnati Streetcar.

Caroline Vickery: Contextualizing Upstate Farms: A preliminary examination of land use and nutrient loading for small farms in the Upstate of South Carolina.

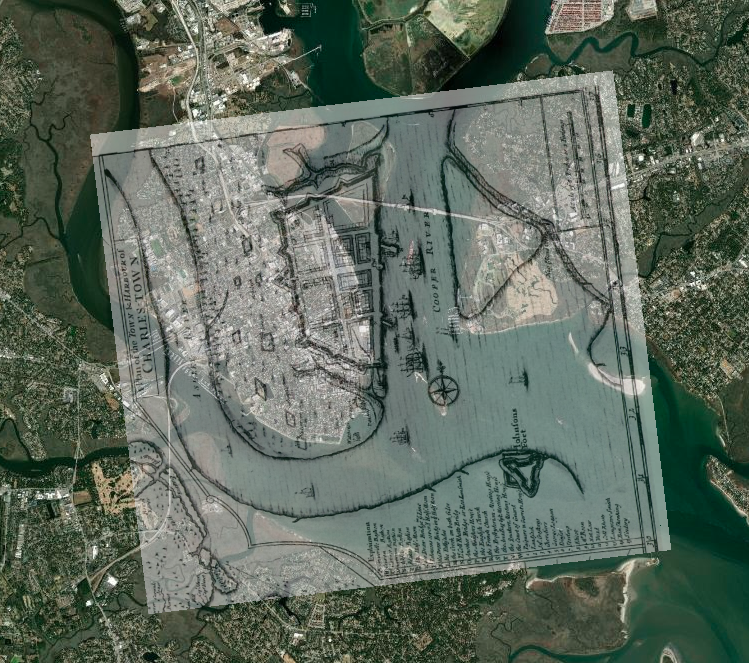

Kylie Gambrill: Understanding Change: The Charleston Harbor — Our perceptions of the environment around us depend upon the cultural context we find ourselves in.

Bennett Dean: Affordable housing and public transportation in Greenville.

Chloe Sandifer-Stech: Recommendations for green space around Enoree Career Center: A study of the influence of tree density on carbon storage.

Jake Gerardi: Land Sparing/Sharing Impacts on Birds: Assessing habitat quality of southern bird species using ecological principles in Greenville watersheds.

Madison Eichhorn: Affordable Housing & Good Jobs – An evaluation of proximity, density, and availability of affordable housing and employment.

Austyn Feigenbaum: Boating Safety Zones and Florida Manatees: An investigation on the relationship between manatee death rates and boating safety zones along the coast of Florida.

I hope you’ve enjoyed seeing the range of student projects and learning more. It’s a pleasure to see all the hard work result in such great studies and stories.